- How the Economic Machine Works

How the Economic Machine Works

In this blog post, I’ll share my reading notes on Ray Dalio’s ‘How the Economic Machine Works’ As someone who’s relatively new to economics, I’m deeply grateful to Dalio for his generosity in sharing his profound insights on the mechanics of economics. His work has significantly broadened my understanding of the subject.

The Transaction-Based Measure on Economic Machine

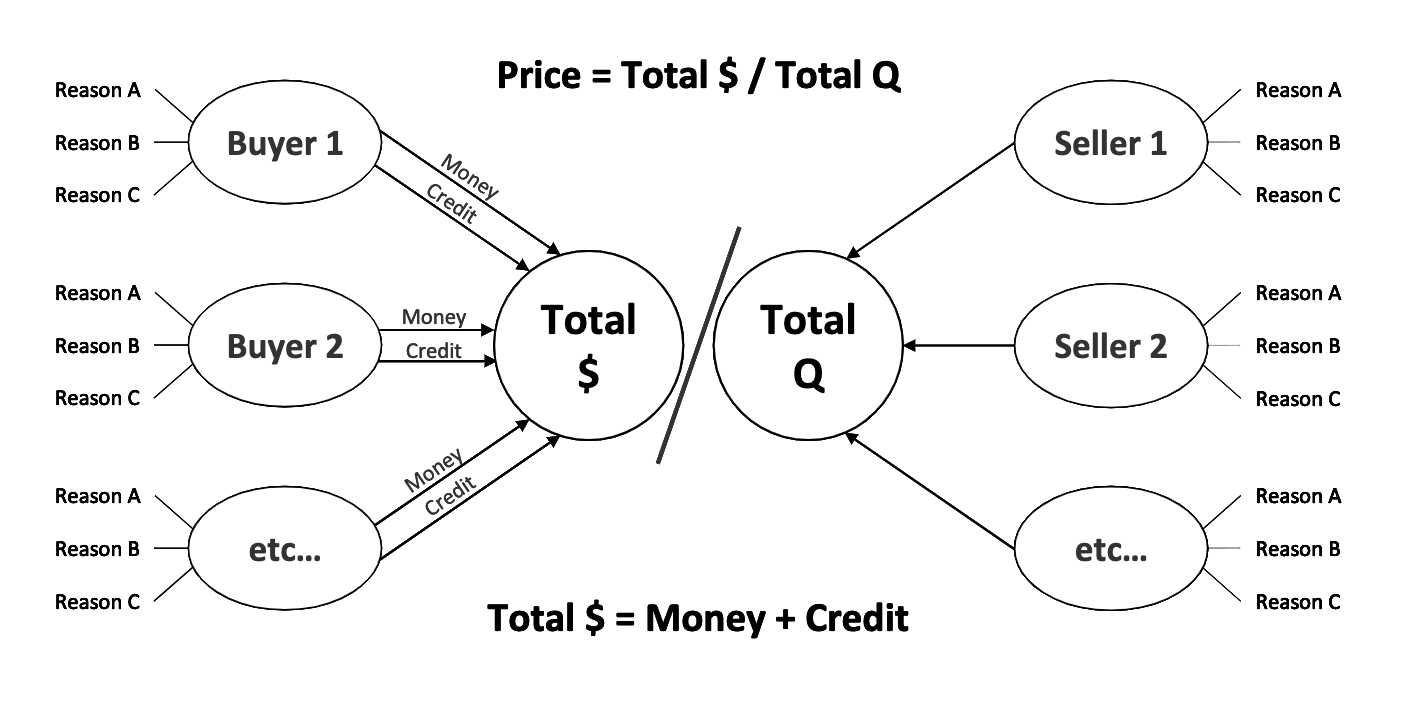

Dalio introduces a foundational concept that diverges from classical economics. He depicts the modern credit monetary-based economy through what he terms the “Transaction-Based Approach.” Through this lens, we can view the economy as a cumulative result of individual transactions.

At the core of economics lies the transaction, which involves two primary entities:

- a buyer, who brings both money and credit to the market

- a seller, who provides a particular good or financial assets.

Moving up in complexity, a specific market represents the aggregated transactions related to a particular good. Broadening this idea, our global economy is essentially the sum of all such markets for every conceivable good.

Apart from categorizing all the markets on their trading qualities, we can also classify the transactions based on the buyers. The buyers can originate from:

- The private sector: Further broken down into households and businesses, both domestic and foreign.

- The government sector: Illustrated by the US, the federal government allocates money to domestic goods and services, while the central bank has the capability to create money and primarily invest in financial assets.

In the transaction-based perspective, assuming a stable supply of the asset quantity, which shows short-term fluctuation, the asset’s price is influenced by both the money and credit expended on it. Given our modern credit-based economy, it’s easy to adjust the supply of spending in the market.

After delving into the concept of the Transaction-Based Lens as posited by Ray Dalio, I aim to briefly outline three key takeaways from the measure on economics, explaining their significance in understanding economic dynamics:

-

Understanding Market Dynamics through ‘Eigen-Transactions’

In a transaction-based economy, one effective approach to dissecting market dynamics is by examining ‘eigen-transactions’, or representative transactions. This viewpoint allows us to interpret the reason for some irrational while deliberate strategies in the principle of traditional supply-demand relationship,two notable instances include:

- The governmental sector, exemplified by the FED, which created an unusual amount of money during the early phase of COVID-19.

- Simultaneously, the private sector occasionally engaged in what appeared to be irrational transactions, the individuals prefer the confidence to condition, to judging the future price of the asset

Given the prevailing circumstances. Such transactions can either ignite a depression economy or fuel an extraordinary bubble.

-

The Role of ‘Credit Creation’ in Bridging Monetary Gaps

Another pivotal aspect underscored by the transaction-based perspective is the concept of ‘credit creation’. When analyzing GDP statistics, some experts propose the concept of ‘velocity of money’ can account for how a GDP is sustained even with a relatively smaller money supply in the market. However, Dalio argues that the overlooked component bridging the gap between GDP and existing money is the formulation of credit within the economy. Interestingly, even if a market experiences an increase in money supply, a significant decline in formulated credit can still lead to price deflation.

-

Market-Participatory Creation of Financial Assets

Contrary to the unique authority of the central bank, which creates money out of thin air, the creation of financial assets can be a more market-participatory action. From the standpoint of borrowers, purchasing financial assets is possessing adequate capital and entering into contracts with productive individuals in the economy, then expecting higher future returns. Conversely, from the debtors’ viewpoint, they are the active producers in the market, confident that they can earn more in the future. Thus, they exchange some of their future earnings for current capital, used to enlarge their production of goods. The creation of a financial asset, that can affect the amount of credit in the market, emerges not from institutional authority but from pure market behavior.

The Template: Three Fundemental Forces in Economic

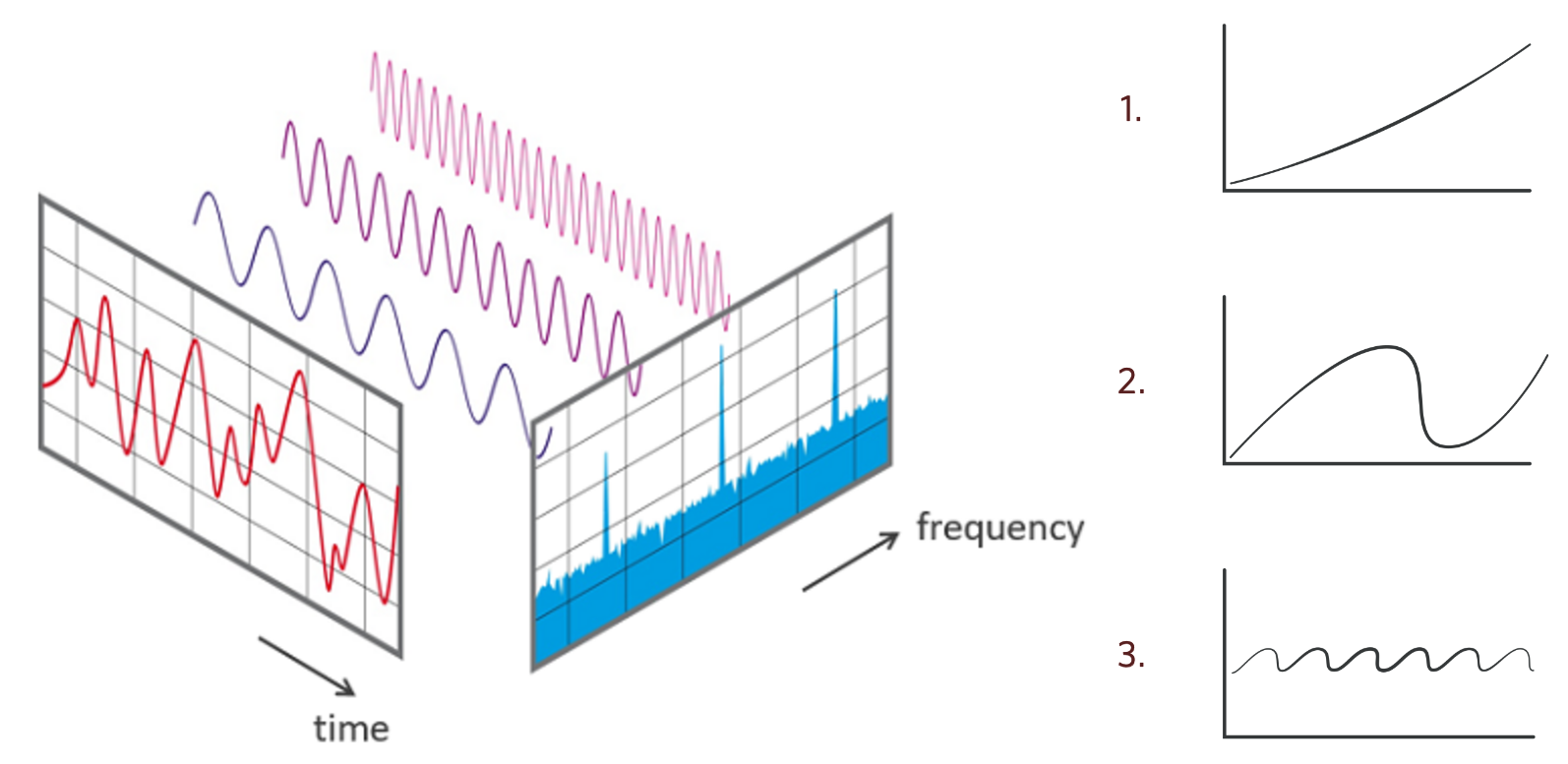

Exploring the working mechanism of economic machines, please envision the Fourier decomposition:

Dalio provides an easy-to-grasp framework with three basis for understanding the economic mechanism. These three bases can roughly understand the workings of the economy:

- Productivity Growth

- Two Debt Cycles:

- Long-term Debt Cycle

- Short-term Debt Cycle

Productivity Growth

In the long run, the intrinsic drive is fueled by productivity growth. The reasoning is straightforward: even in a modern economic system with credit, the generated credit needs to be repaid in the future. In contrast, the advancements in science and technology are enduring assets that will not be erased from the world. Furthermore, from the viewpoint of the macro-economic machine, with the growth of productivity, the capital invested in the past will be repaid more easily in the future.

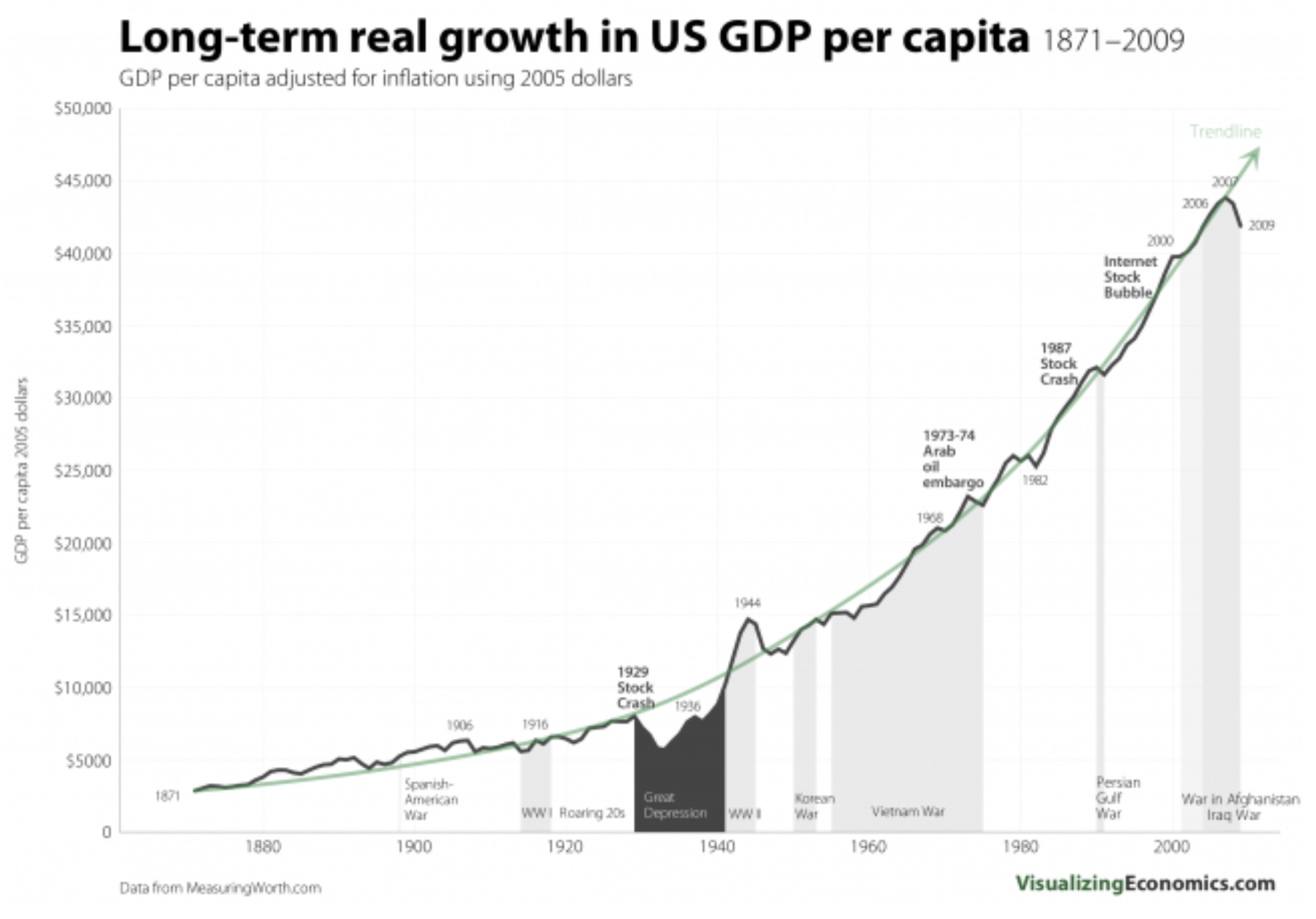

Taking the history of the US as an example, the image below shows the GDP per capita adjusted for inflation. From the data, we observe that the growth of productivity is relatively a steady process. Aside from the Great Depression period, economic downturns are less pronounced:

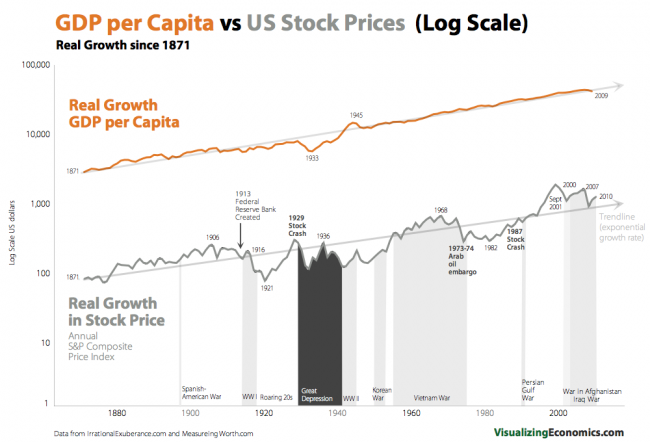

Productivity growth, as depicted in the domestic market of the US, presents a macro-level perspective. Although individuals may have faced greater challenges during the Great Depression, thanks to the diligent work of the author of the diagram, we can compare the stock prices, which are relevant to individual people:

Even when adjusted on a log-scale, the equity asset price experiences severe volatility, compared to the macro productivity measure: the GDP per capita in the market. Yet, the equity asset price clearly holds a strong relevance to the ordinary person in the economics machine. The question arises: during the Great Depression, did people suddenly forget the methods of productivity, or did the symbols of productivity growth, these machines, suddenly revert to versions from decades prior? In analyzing this issue, we should consider another fundamental force in the economic machine: the two debt cycles.

The Two Debt Cycles

Debt cycles emerge from the use of credit in economics. When we observe human society as a holistic entity, we notice that economic cycles are repetitive patterns in history.

To illustrate the patterns do exist, Dalio uses Monopoly as an approximation to the real-world economic machine. This is due to the design of Monopoly: in the early stage of the game, ‘property is king’. As cash in the market decreases, the game enters the second stage where ‘money is king’. Furthermore, with the virtual introduction of a ‘bank’, which offers money with a deposit rate reward, and lends money to potential debtors, there will lead to the game to an interesting stage, where the borrowers squeeze the bank’s deposit while the debtors fail to pay back, symbolizing a debt crisis in the Monopoly game.

Monopoly, with its clear rules written in the reference books, serves as a simplified model. For the real-world economic machines, our task is to extract some signs and rules. Under the transaction-based measure, we can redefine prosperity and depression, then examine money and credit to understand the monetary system.

Modern Monetary System Through the Transaction-Based Measure

The two fundamental elements in modern monetary systems are money and credit. For the sake of fiscal policy flexibility, the government shifted from the previous monetary system, which abandoned the previous commodity element, such as gold.

Money

In the Transaction-Based approach, money is a means to settle transactions. Compared to credit, which gradually settles payments in the future, money facilitates payment in the current timestamp. Besides, Dalio separates the total spending in the US economy into two categories in the transaction-based measure: money, which stands for the currency and reserves in existence totals about $ 3 trillion, while credit amounts to about $ 50 trillion, 15 times more than the money, at his writing times. This implies:

- Many people actually pay with credit when they settle their transaction

- During a debt crisis, many people may discover their payment ability is less than the obligations of credit payment.

Credit

Aside from the money that printed by the central bank, individuals in the economics machine will also use capital formation to create the credit, seemingly out of thin air. The borrowers and the debtors, enter a contract to repay at a scheduled future time, the formed credit can be spent in the market, with no distinction from money.

In an ideal process, the borrowers increase their productivity at a pace faster than the conventional payback rate. The debtor can benefit from the excess between their advanced producivity and the payback rate. And the borrowers, tend to agree on a payback rate in the contract that’s faster than the productivity growth rate of the whole market.

Delving deeper into the ideal process, Dalio uses a simple example about a whitewasher in his notes. But I want to retell his story, withnot losing the essence:

- Dalio invites the whitewasher to paint his office, and they make a paper contract. Remember, it’s the famous Dalio.

- The whitewasher actually has no adequate money to buy the materials, but he shows the bank his contract. The manager of the bank, who is a friend of Dalio, lends the whitewasher the money.

- With the money, the whitewasher goes to the building materials salesman. Instead of buying the materials with the full amount, he pays partially, with the remainder in a contract to pay in the future.

- Finally, the whitewasher completes the task excellently, everyone at Bridgewater admires Dalio’s new office. So, the whitewasher gets many contracts from Bridgewater’s employees. Remember, he bought the materials on credit, so he can rush back to the materials salesman, buying a large amount of materials to prepare for the office painting contracts at Bridgewater.

- Is the story over? Nope, remember the bank manager and the salesman? The bank manager can consolidate the whitewasher’s credit (A rank) into an asset package, to sell in the debt market. And the material salesman, finding a steady buyer, becomes confident enough to negotiate better futures contracts with his material manufacturers.

The money paid in the ideal process is much less than the credit, but everyone in every chain of the process is pleased with the outcome. The whitewasher gets money, the bank manager earns from interest and the asset package, the material sectors get a steady order, and Dalio enjoys his new office. This is the power of credit, it alleviates the creation of demand from the burden of commodities or money in the previous monetary system. The creation of credit solely depends on the confidence of borrowers and lenders in the market. It indeed accelerates the positive productivity process. With the ideal process permeating the whole market, the market is in a self-reinforced prosperity state.

However, if you follow the news about real estate deleveraging in China, you can easily map the respective characters in China’s real estate market to the characters in the previous story. Abuse of credit can lead to disasters to the private sector, then hinders economic development.

Aside from the confidence in a win-win structure during a capital formation, another consideration for investors is liquidity.

- On Macro-level:

$3 trillion in money, compared to about$50 trillion in credit - On Micro-level: as depicted in the previous story, the money spent in the process is less than the credit

At a certain point, when a large number of people unilaterally convert financial assets to money, the price of financial assets will crash.

The Evolution of Monetary Systems

With the explored two foundational elements—government-issued currency and market-formed credit, we can trace the evolution of monetary systems with a transaction-based perspective.

-

Barter System: Initially, societies operated on a barter system, where goods and services were exchanged directly. However, the limitations of this system, especially the need for a double coincidence of wants, eventually necessitated the adoption of more universally accepted mediums of exchange.

-

Commodity Money System: Precious metals like gold, silver, and copper gained popularity as mediums of exchange. Their intrinsic value, combined with their scarcity, ensured stability in supply. The defining characteristic of this era was the absence of a centralized banking system capable of managing money supply, with credit playing a minor role in commerce.

-

Gold Standard: With the emergence of nation-states, central banks were established to issue currency. This currency often had a fixed exchange rate to a commodity, like gold, held in reserve. The central bank could then manage the national money supply within the constraints of their gold reserves, pledging to maintain the convertibility at the set rate. On the flip side, this system allowed central banks to expand the money supply with the expectation that they could defend their currency during potential squeeze on their gold reserves.

-

Fiat System (Pure Credit System): The advancement of financial systems led to the recognition that credit could function as money in transaction. Governments, recognizing the limitations of commodity-backed currency on economic growth, transitioned to fiat systems where currency value is based on government decree and public trust in its stability. In the U.S., the transition occurred in stages: domestically during the Great Depression under FDR, who recalled gold to expand fiscal policy leeway, and internationally with the end of the Bretton Woods system during the Nixon Shock, after which the U.S. dollar’s value was tied to the economic might of the U.S. and its demand as a reserve currency in global trade.

The trajectory of monetary evolution underscores a shift towards:

- Increased Governmental Control: Removing the commodity anchor allows governments to manage national currency more freely.

- Credit as a Substitute for Commodity: Trust and creditworthiness in transactions have replaced the intrinsic value commodities provided, empowering economic exchanges and growth.

The Two Debts Cycles

With the introduction of money and credit, along with the evolution of monetary systems, we can now delve into the two debt cycles. While the long-term debt cycle is less commonly discussed in economic literature, the short-term cycle is more familiar to the general public.

Long-Term Debt Cycle

At the outset of this section, Dalio uses an advanced version of the game Monopoly, which includes a bank, to illustrate the basic mechanics of economic cycles. In this enhanced Monopoly game, the long-term debt cycle refers to a process where the economic system gradually pushes the debt level to an unsustainable extent, eventually leading to a situation where no strategies can sustain credit growth. In other words, the long-term debt cycle ends with a systemic run on the banking system within an economic framework.

Thus, in the context of a fiat money system, the long-term debt cycle is actually a rarity in federal history. The worst-case scenario, like the Great Recession, could potentially escalate to a crisis akin to the Great Depression in a fiat system. Furthermore, to provide empirical evidence, Dalio draws on various economic indicators from the Great Depression, although it’s important to note that the monetary system when the Great Depression started was gold-based.

Dalio included the long-term debt cycle top occurs in two logic indicators:

- High levels of debt burden

- Ineffective monetary policy in stimulating credit growth

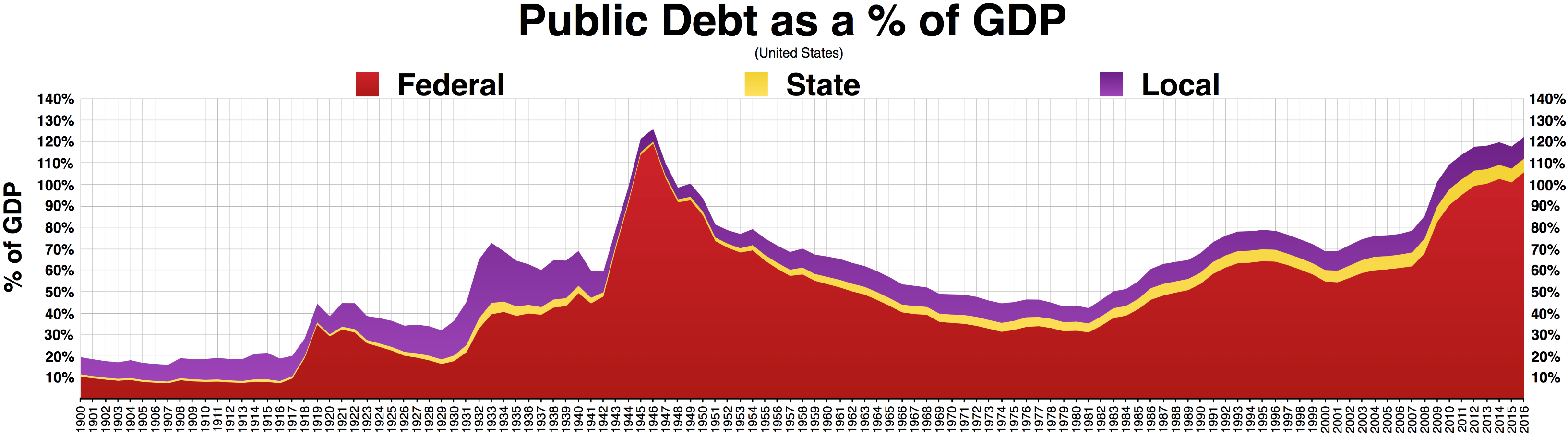

Regarding the first point, excluding the exceptional periods of WWI and WWII, we observe a significant debt burden level during the Great Depression. To address the peak of the long-term debt cycle during this era, as part of his New Deal, FDR removed the U.S. from the gold standard domestically, expanding the government’s fiscal policy capabilities. The Roosevelt New Deal, a combination of various fiscal policies, successfully reversed the reinforcing downturn trend of the federal system. Focusing on the four periods during President FDR’s tenure, an analysis of the debt-to-GDP ratio reveals some interesting points:

- Under the Roosevelt New Deal, there’s a noticeable increase in local debt, likely attributable to public works projects. These projects provided employment opportunities and elevated the U.S. infrastructure level. Iconic constructions of the era like the Hoover Dam, are still operational today.

- Regarding the impact of World War II, particularly after the attack on Pearl Harbor in 1941, there was a shift from local and state debts to federal debts. This restructuring of federal debt, facilitated by the Public Debt Act of 1941, was part of a broader wartime strategy that centralized fiscal authority and economic planning at the federal level to mobilize resources for World War II. Following WWII, the world transitioned to the Bretton Woods system, where the centralization of fiscal power concerning debt remained with the federal government until today.

As we delve into the macro-level analysis of high debt burdens, we encounter the second critical issue: the diminishing effectiveness of monetary policy in stimulating credit growth.

This ineffectiveness often stems from a decades-long cumulative leveraging process. To illustrate, consider the concept of a ‘debt gap’ in the context of household debt. The household sector is fundamental to the economic machine at the domestic level, underpinning the government, financial, and corporate sectors. When households are stretched to their financial limits—a situation that can be quantified as a ‘debt service gap’—the closer the total household debt level (both the aggregate amount and annual service costs) comes to this gap, the less effective monetary policy is at stimulating further credit growth.

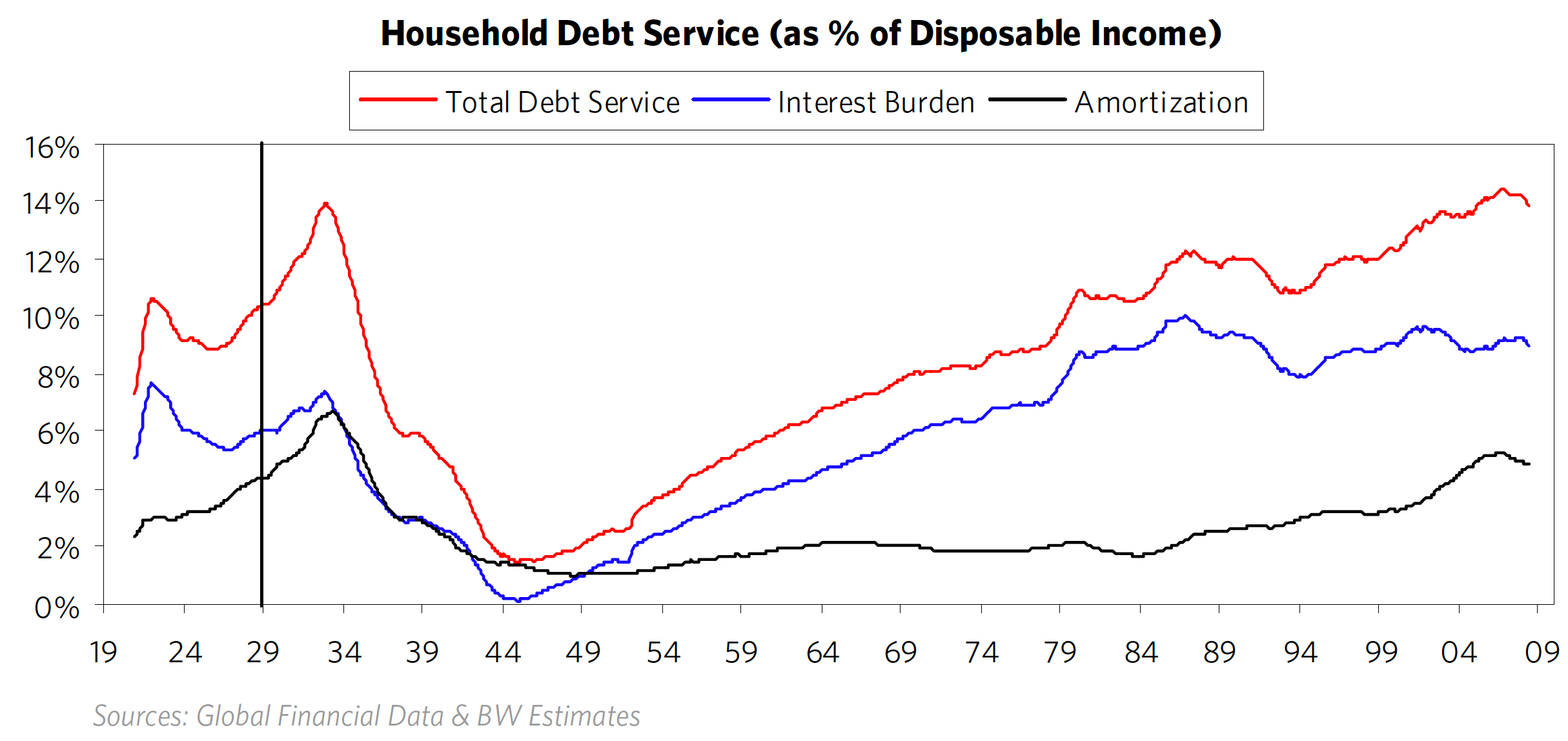

To depict this phenomenon, Dalio presents a graph on the household debt service to disposable income ratio.

-

As the Roaring Twenties concluded, U.S. household debt service was approximately 10% of disposable income, with much of the credit creation concentrated in the stock market. However, between the stock market crash and the robust implementation of the Roosevelt New Deal, the household debt service level did not immediately drop; rather, it increased due to a reduction in income levels. Mere statistics can’t fully express the real-life tragedies of that period.

-

The gap persists even within a fiat monetary system. However, thanks to the system’s flexibility, the government can elevate the gap or employ adaptive fiscal policies to avert crisis-level defaults within the economic machine.

- At the onset of the Great Recession, the household debt service level was again at a critical gap, based on conditions at the time. Yet, with the fiat system and untypical fiscal policies like Quantitative Easing (QE), this level was managed, helping to prevent an economic collapse akin to the Great Depression.

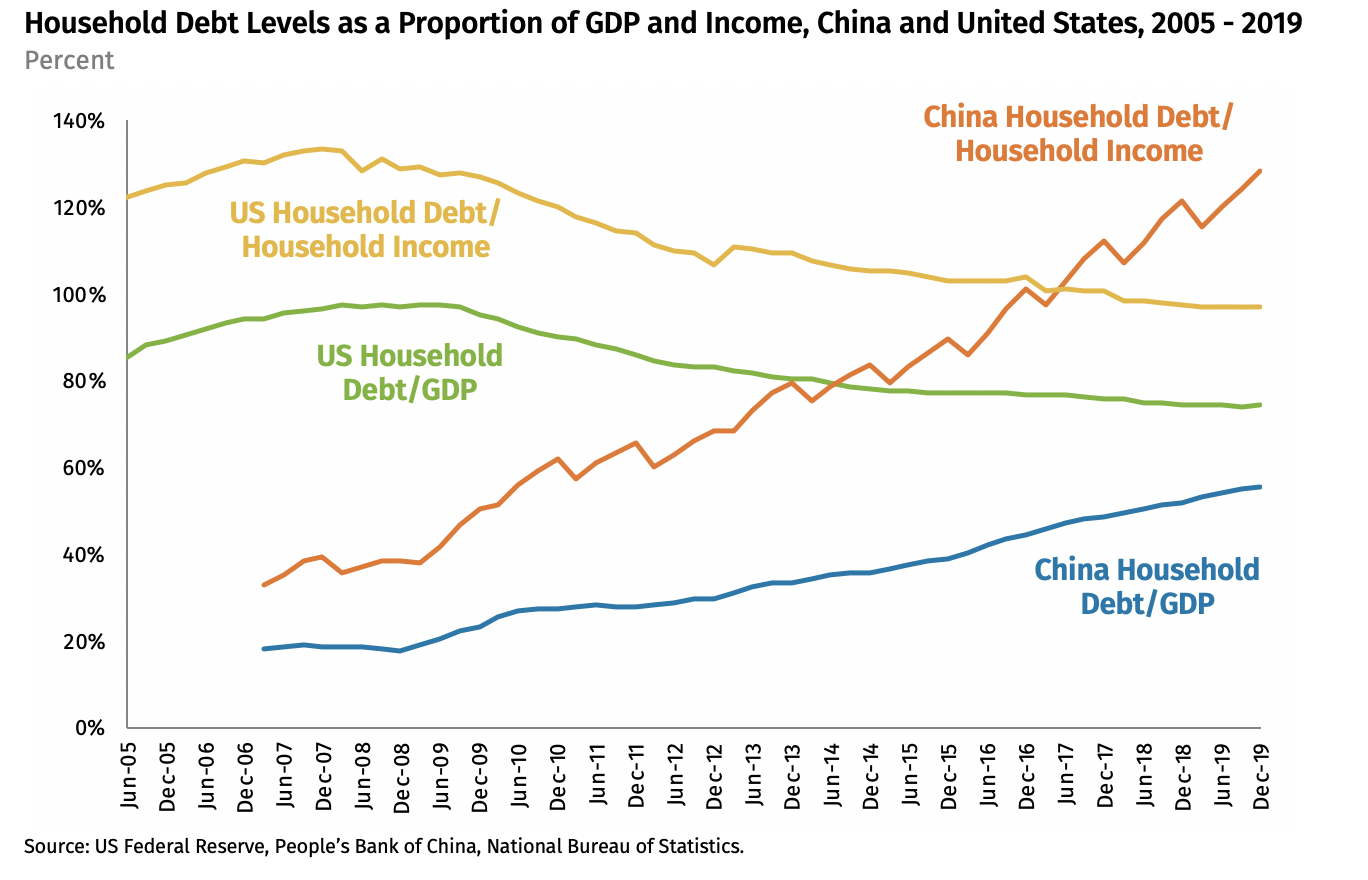

- The Rhodium Group’s research on household debt levels indicates that in both developed countries, like the U.S., and developing ones, such as China, when the ratio of Household Debt to Household Disposable Income reaches a relatively high level—around 120%—the household sector shows signs of strain, becoming increasingly resistant to additional debt. Consequently, stimulation policies, such as those targeting the real estate market, lose their effectiveness.

It’s easier to understand that GDP is a macro-level metric, while household disposable income is a micro-level indicator, which more acutely reflects the economic pressures on individuals.

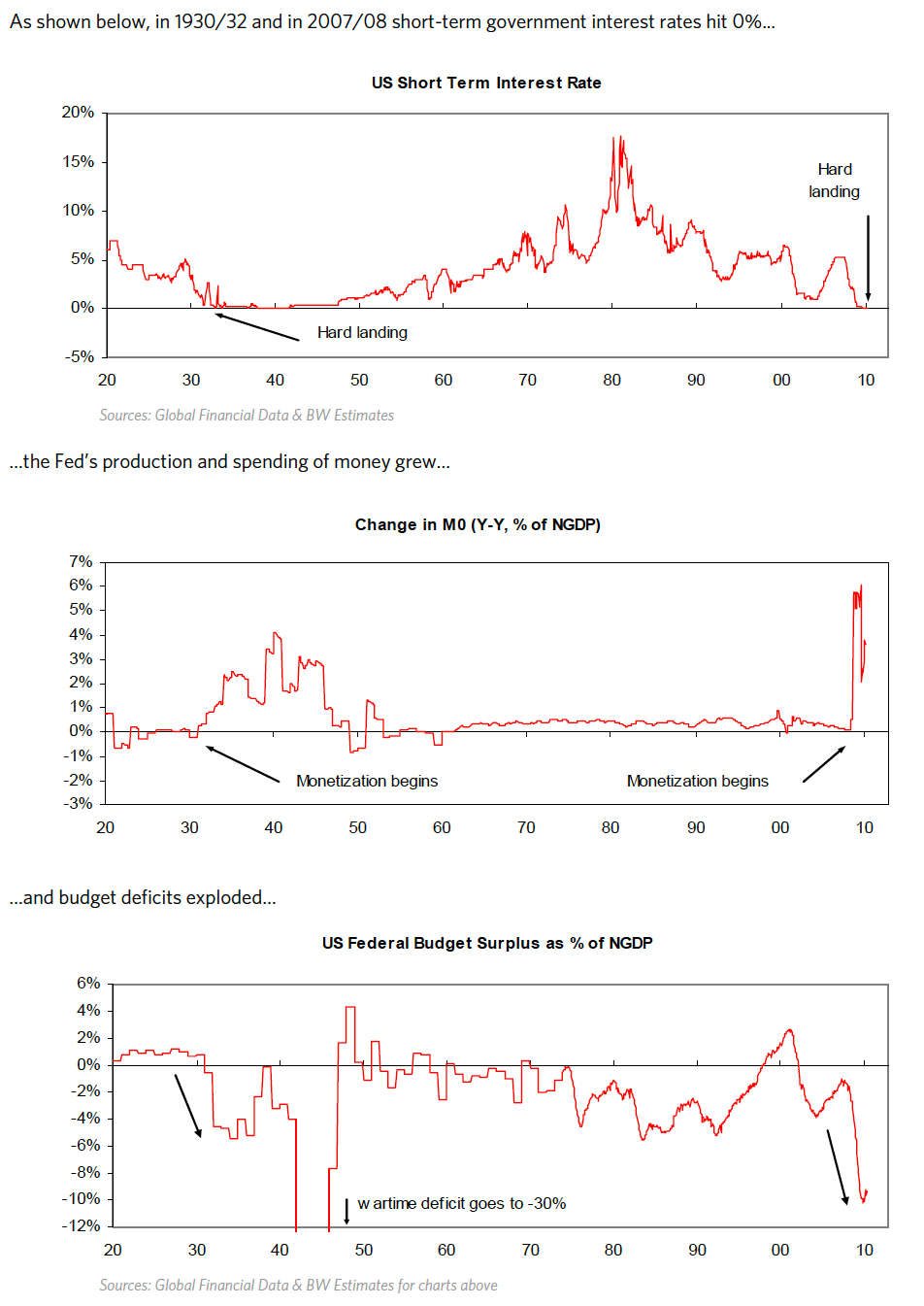

In discussing the indicators that signal the peak of a long-term debt crisis, Dalio underscores the underestimated perils of scenarios marked by financial asset bubbles and low inflation—conditions that can cause a bank run within the economic system. Historical events such as the Great Depression, Japan’s Asset Price Bubble, and the 2007-2008 Global Financial Crisis illustrate the catastrophic potential of financial asset crises on the entire economic machine. Dalio identifies a critical juncture for these crises: the point at which fiscal policy has no room to maneuver, characterized by interest rates approaching 0%. Given the nature of financial assets, which are often leveraged with minimal money and substantial credit, the consequences of a run in such a context can be devastating.

At the catastrophic turning point of the long-term debt cycle, four fundamental forces intertwine and dominate the economic machine before it can alleviate its debt burden and reenter a healthier state:

- Debt reduction through defaults or restructuring

- Austerity measures

- Wealth redistribution

- Debt monetization

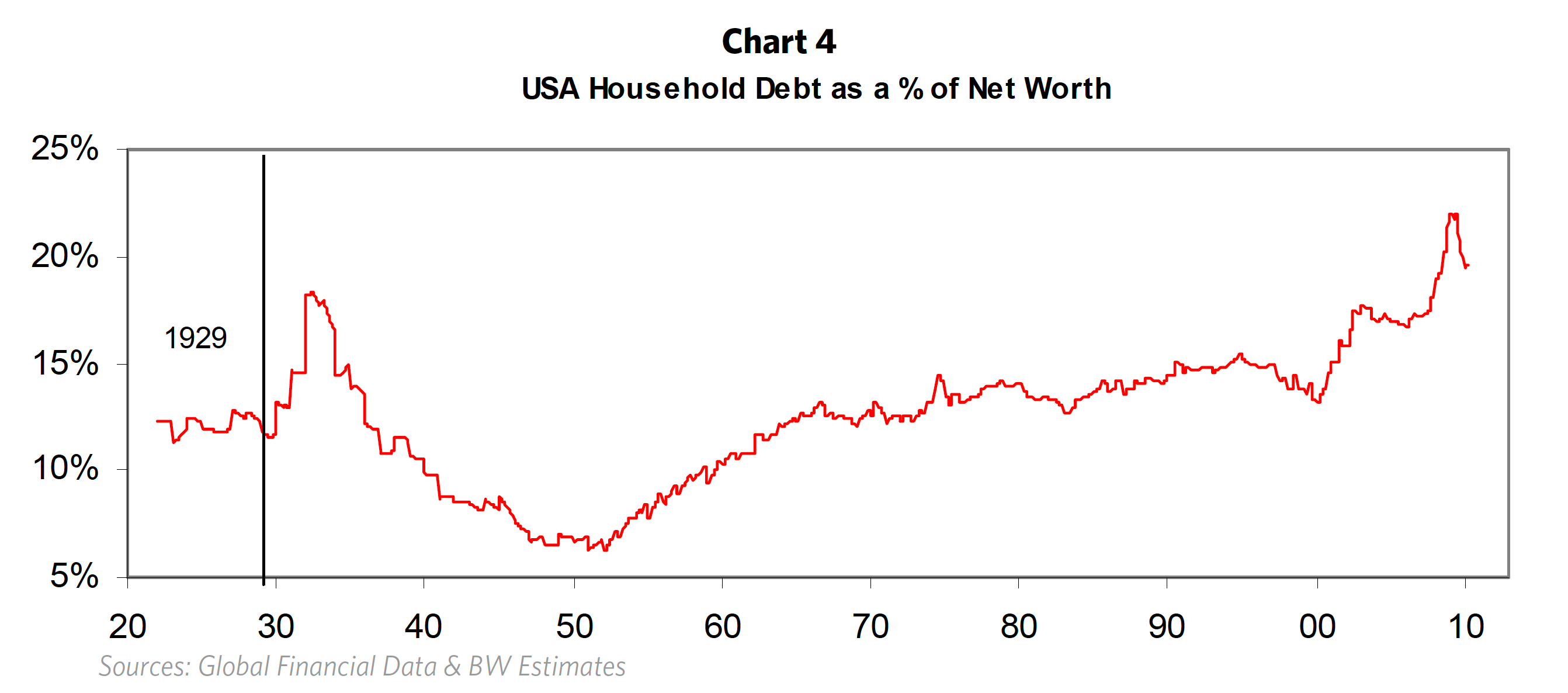

Depressions represent the contraction phase of the deleveraging process, with debt reduction—especially defaults—and austerity measures taking precedence. During this contraction phase, individual income levels inevitably fall as all sectors adopt austerity measures to protect their property. Additionally, the shrinkage of net worth can be explained by the idea of borrower creditworthiness, which hinges on two factors: their disposable incomes and their net worth. Similar to the ascent of the fiat monetary system, both disposable incomes and net worth face a downward spiral, causing the creditworthiness of borrowers to decline.

Coupled with the Household Debt to Disposable Income ratio, the contraction phase after a long-term debt cycle peak reveals an increase in individual debt levels during the depression stage. The decline in income and net worth occurs more rapidly than the pace at which debts are defaulted on. Again, mere statistics cannot fully convey the grim reality of those times. As borrowers’ creditworthiness declines, debtors tend to retract funds, which, under the properties of a fiat money system, is problematic because actual money in circulation is much less abundant than credit. It’s not a matter of morality, but debtors’ fear of defaults indeed cause a severe cash flow crisis within the economic machine.

During this depression stage, the private sector often lie down, adopting austerity measures. Conversely, a responsible government sector will implement counter-cyclical fiscal policies to bolster market spending. Dalio outlines three government actions during such times:

- Initiatives to encourage credit creation

- Relaxation of regulations compelling debtors to service their debts

- Money printing and spending on goods, services, and financial assets

The figures represent easing credit creation, money printing, and spending, respectively. Regulations on debt servicing are not within the purview of the Federal Reserve and are challenging to quantify.

When these three anomalies—credit easing, increased government spending, and relaxed debt servicing regulations—occur simultaneously, it’s a clear sign that the economic machine is damped in a depression. Because these expansionary measures originate from the government sector, the improvement in the private sector’s debt level will lag behind. Moreover, while the analysis of debtors is rooted in their psychology, statistical data on populations reveal that until the private sector’s debt levels decrease to a sustainable level, the contraction will persist. During this stage, the will of most in private sectors, inevitably compel the government to intervene, either through increased fiscal budget or by the central bank monetizing the debt. Delving into the monetization of the debt, which central bank inject money into the economy includes purchasing government securities and private assets such as corporate securities, equities, and other financial instruments. The goal of these actions is to mitigate the contraction of credit, by an exceedingly increase money in economics machine.

Wealth redistribution often comes into play as governments use taxation as a tool to balance budgets and address income inequality. Governments may impose taxes on the wealthy through various means, such as income and consumption taxes. While these taxes can bolster government revenues, they may also lead to a decrease in economic activity. This is because as the government draws on cash flows, it can inadvertently harm the normal functioning of businesses, prompting the wealthy to become more defensive and protective of their assets. Thus, an increase in government revenue can coincide with a direct loss in industries predominantly owned by wealthier individuals.

From global perspective to consider wealth redistribution, wealthy individuals and corporations might attempt to safeguard their assets by converting them into other currencies or investing abroad if they perceive a threat from increased taxation or less favorable fiscal policies. This can lead to capital flight, which poses a significant risk to the foreign exchange stability of the country’s economy. Countries with current account deficits are especially susceptible to such movements of capital, often prompting their central banks to print more money, which can devalue the currency. A depreciating currency may, in turn, trigger a rush towards more stable foreign currencies or inflation-hedge assets. Ultimately, the capital formation within the domestic market may diminish, outweighing the gains from taxes or hedging activities.

In summarizing the long-term debt cycle, a key area of study is the deleveraging process. During the contraction phase of deleveraging, austerity measures and debt reduction typically take precedence. This stage can last around two to three years before the economy begins its slow journey to recovery. At this point, it’s crucial for the government to implement fiscal policies designed to maintain nominal interest rates below the rate of nominal growth. Such policies aim to alleviate the overall debt burden, fostering a more sustainable economic environment.

Short-term Debt Cycle

The short-term debt cycle, also known as the business cycle, is primarily influenced by the monetary policies of central banks. These policies typically:

- Tighten under certain conditions:

- High inflation

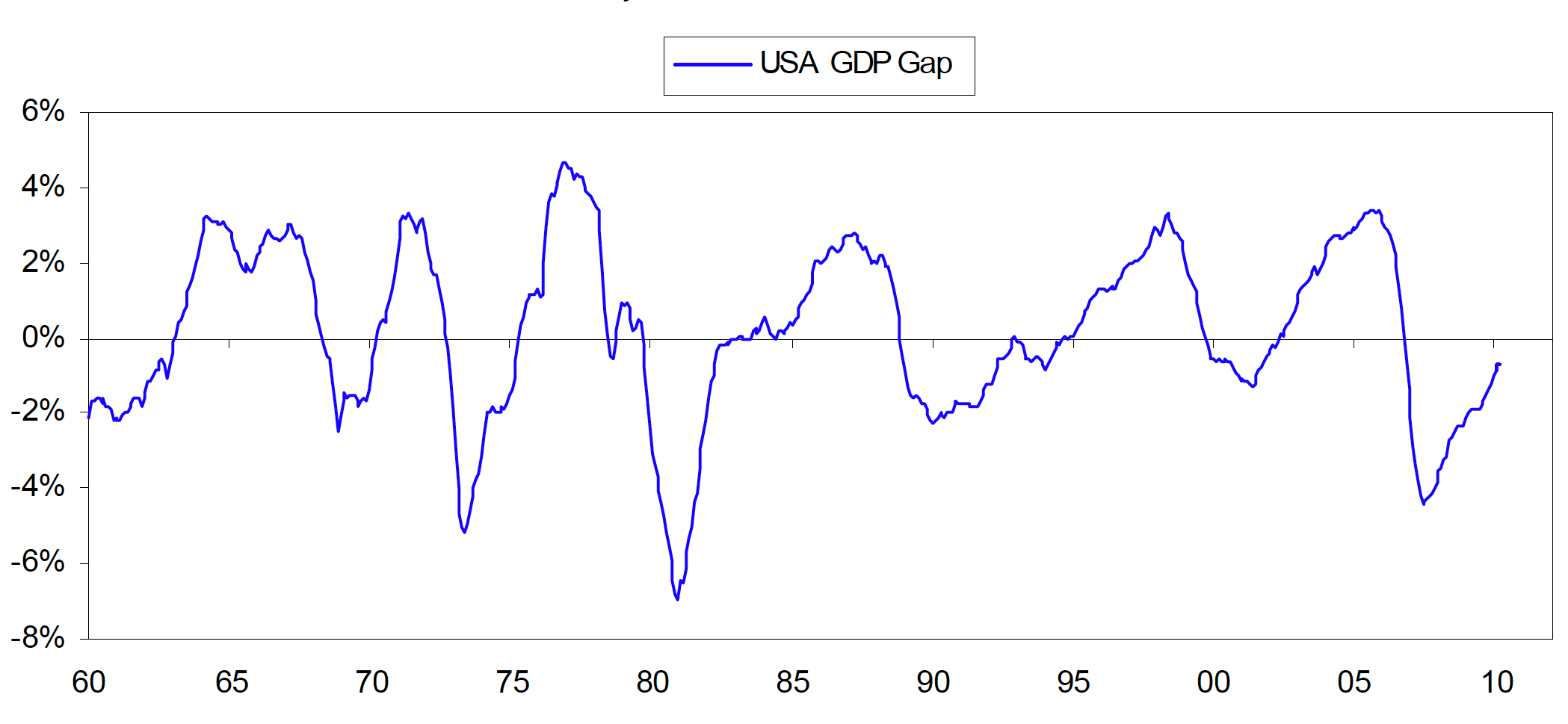

- Signs of a cycle peak indicated by GDP gap, capacity utilization, and the unemployment rate.

- Excessive credit growth

- Ease when the opposite conditions are present.

As shown in the figure, the short-term debt cycle exhibits a more periodic nature compared to the longer-term cycle. Dalio divides the short-term debt cycle into six phases—four in expansion and two in recession:

- The “Early-Cycle” (lasting about five or six quarters): Following the contraction phase of the previous cycle, this phase typically features:

- High growth (over 4%)

- Low inflation

- Rapid credit growth

- Increased comsumpution, especially in interest rate-sensitive items

- The “Mid-Cycle” (lasting around three or four quarters): Characterized by a substantial slowdown in growth (to around 2%):

- Inflation remains low

- Slower growth in consumption

- Decline in the rate of inventory accumulation

- The “Late-Cycle” (beginning about two and a half years into expansion, depending on how much slack existed in the economy at the last recession’s trough): Growth peaks after this stage, with economic growth accelerating to a moderate pace (around 3.5-4%):

- Strong credit and demand growth, but capacity constraints emerge due to declining inventory accumulation

- Inflation trends higher

- Interest rates start to rise

- The “Tightening Phase” (the peak of expansion):

- Central banks respond to inflation problems with tighter fiscal policy

- Interest rates rise, and money supply contracts

- Early Part of the Recession:

- Economic contraction

- The return of slack, as measured by the GDP gap, capacity utilization, and unemployment rate

- Late Part of the Recession:

- Ongoing economic downturn with controlled inflation

- Interest rates decline

While Dalio also highlights the flexibility in analyzing the short-term debt cycle:

- The sequence of phases can depend on specific events, not just a simple timeline

- The style of central bank policy (aggressive vs. conservative) can affect the timeline

- Structural factors such as China’s entry into the world economy, wars, and natural disasters also play a role

Reference

[1] Ray Dalio 2015. How the Economic Machine Works

[2] Wikipedia National debt of the United States

[3] Logan Wright and Allen Feng 2020 COVID-19 and China’s Household Debt Dilemma

[4] Barry Ritholtz 2011 Long Term Stock Market Growth (1871-2010)

[5] VisualizingEconomics 2011 Long-term real growth in US GDP per capita 1871-2009